January 2024 Monthly Report

In this blog post, we discuss our January 2024 report and provide more information on how to interpret the results. The PDF report can be found at the end.

Key findings:

- The median fentanyl concentration found across all drug categories was 15.6%

- The median fluorofentanyl concentration found across all drug categories was 7.7%

- Carfentanil was found in 3 expected opioid - down samples with a median concentration of 0.2% and maximum concentration of 0.9%

- Benzodiazepines were found in 52.6% (150/285) of expected opioid-down samples

- Bromazolam, the most common benzo found within opioid-down, was found in 110 opioid-down samples with a median concentration of 4.7% and maximum concentration of greater than 25.0%

- Xylazine was found in 20 expected opioid - down samples with a median concentration of 8.2% and a maximum concentration of 40.2%

Insight for the January 2024 Monthly Report

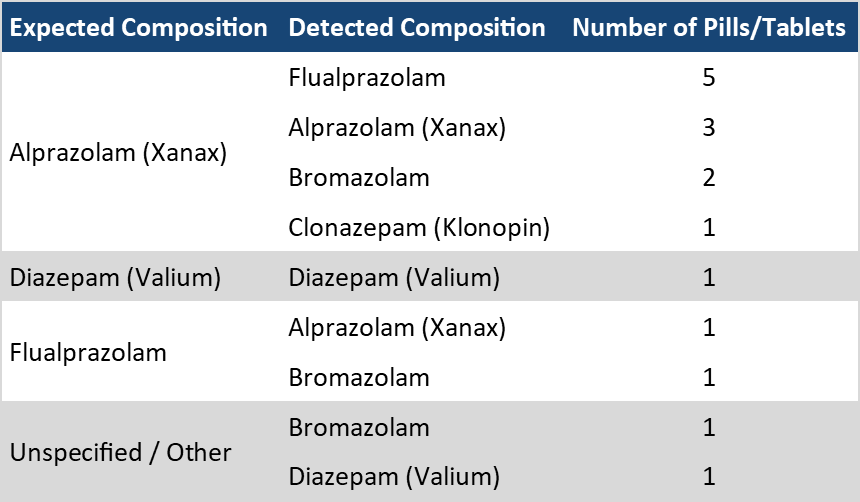

This blog, and the associated pdf report, breakdown our sample counts into six categories:

- samples received through direct service provision in Victoria, where service users are bringing samples into the Substance storefront. These samples are labelled as “Substance” samples in the figures/tables of this blog post

- samples received through direct service provision in Campbell River, where service users bring samples either to the Vancouver Island Mental Health Society (VIHMS) or Campbell River AVI Health & Community Services. These samples are labelled as “Campbell River”

- samples received through direct service provision in the Comox Valley, where service users are bringing samples to AVI Health & Community Services in Courtenay, BC. These samples are labelled as “Comox Valley”

- samples received through direct service provision in the Cowichan Valley, where service users bring samples to the Duncan Lookout Society OPS in Duncan, BC. These samples are labelled as “Duncan”

- samples received through direct service provision in Port Alberni, where service users bring samples into Port Alberni Shelter Society’s OPS. These samples are labelled as “Port Alberni”

- samples received through indirect service provision, where samples are collected through no-contact drop-off envelopes, are collected by harm reduction workers and other community members at supported housing sites, overdose prevention sites, supervised consumption locations. These samples are labelled as “Outreach” samples in the figures/tables herein.

Drug types

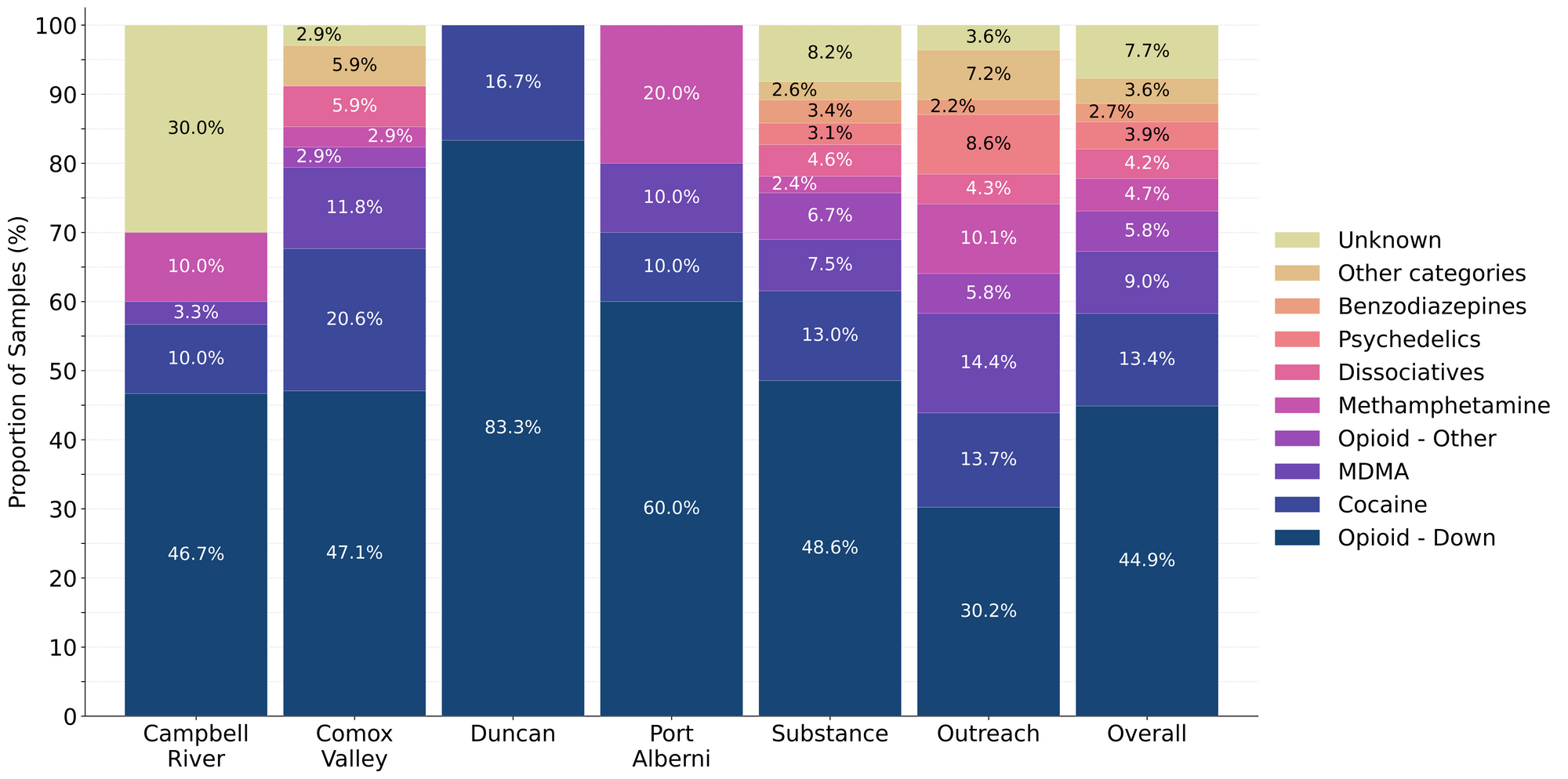

Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of each expected drug category checked, split by sample collection location/method.

The Sample Breakdown

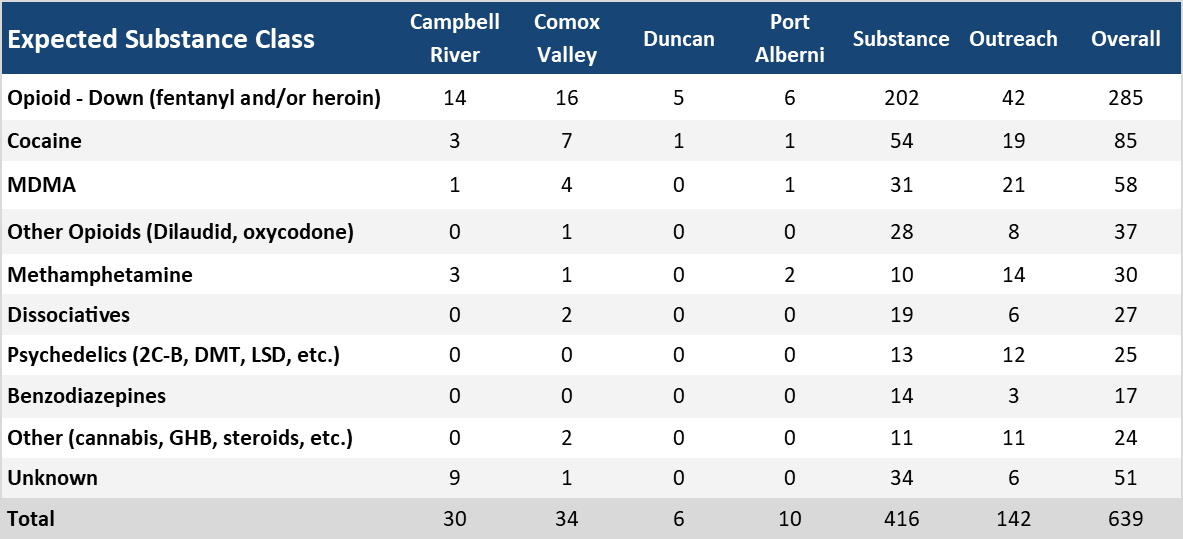

For the majority of samples checked, we confirm the presence of the expected drug with no additional active compounds detected above the limitations of the drug check. The bar charts below highlight a few classes of drugs, differentiating samples where only the expected active component was detected - from situations when other unexpected active components were detected.

Ketamine

100% (27/27) of expected ketamine samples checked in January were confirmed to be ketamine with no other active compounds detected.

Cocaine

89.4% (76/85) of expected cocaine samples (50 cocaine HCl/soft, 1 cocaine base/hard/crack, 1 cocaine HCl/soft and benzocaine) were confirmed to be cocaine with no additional active compounds detected.

5 samples contained an active component in addition to cocaine (Victoria (5), Campbell River (1)):

- 3 samples contained cocaine base in addition to phenacetin

- 1 sample contained cocaine base and fentanyl or a fentanyl analogue via strip test only. This is likely due to cross contamination with another sample.

- 1 sample contained cocaine HCl and levamisole

2 samples did not contain cocaine but instead contained an unexpected active:

- 1 sample contained ketamine instead of the expected cocaine hcl

- 1 sample was consistent with a down sample and contained bromazolam, fentanyl, fluorofentanyl and xylazine instead of the expected cocaine base. Cocaine base samples are often most described as “white (or clear) crystals, this sample was described as "purple pebbles"

The remaining 2 samples did not have active components detected.

Methamphetamine

93.3% (28/30) of expected methamphetamine samples checked were found to be meth with no other active compounds detected.

Out of the remaining two samples, one contained methamphetamine in addition to amphetamine. The other remaining sample contained cocaine HCl instead of methamphetamine.

MDMA/MDA

86.2% (50/58) of expected MDA/MDMA samples checked were confirmed to be MDA (1 sample) or MDMA (49 samples) as expected.

3 expected MDMA samples (2 from Victoria, 1 from Campbell River) contained MDA in addition to MDMA:

- 4 samples contained an unexpected active component

- 3 samples contained MDMA instead of MDA

- 1 sample contained MDA instead of MDMA

1 sample did not have any active components detected and instead was found to only contain lactose (a sugar).

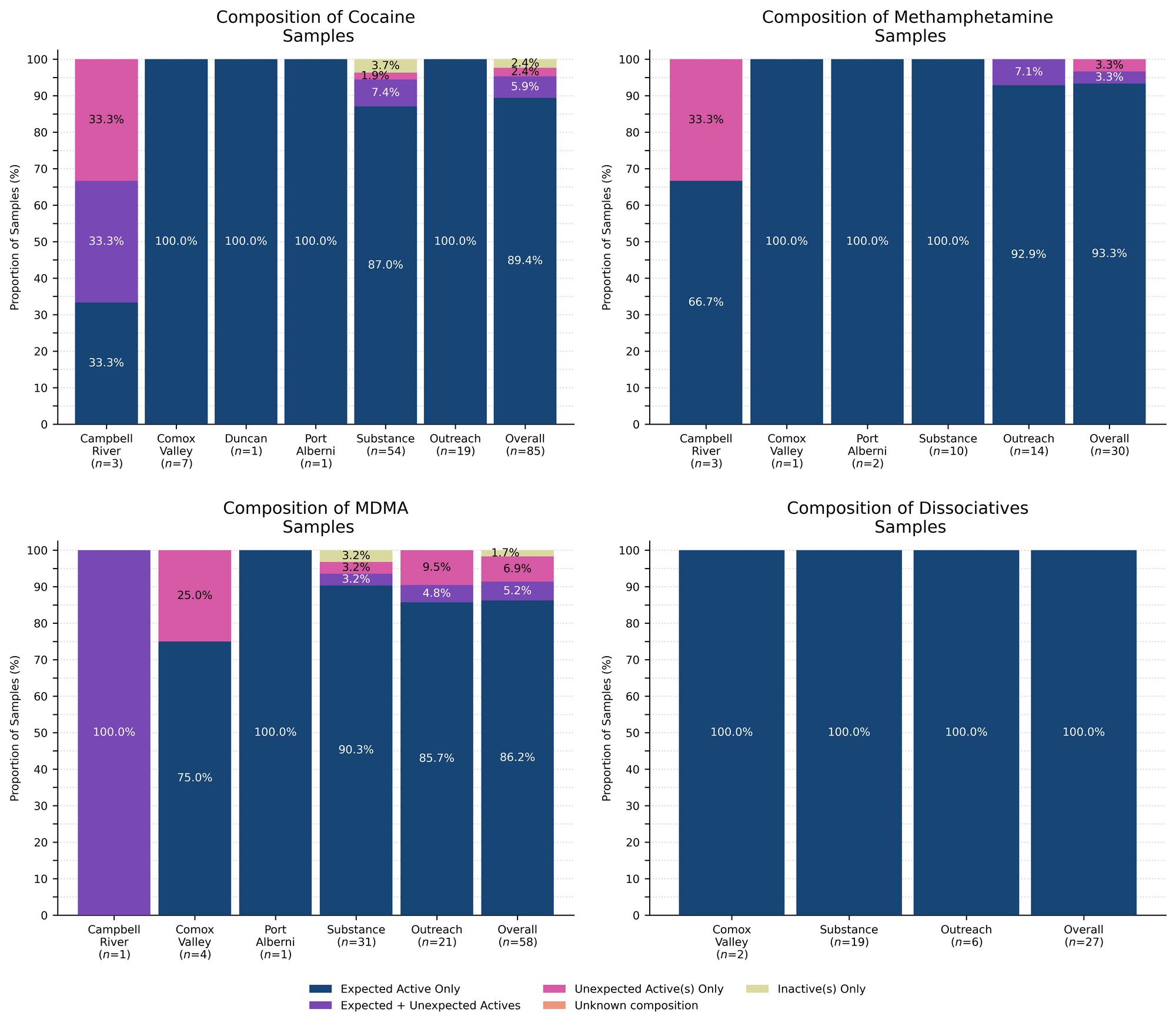

Benzodiazepines (n=17)

87.5% (15/16) of the expected benzodiazepine samples checked in January came to our service sites in the form of pressed pills with the following expected and detected compositions:

The remaining sample had the following expected and detected compositions:

- 1 sample expected to be an unspecified benzodiazepine, contained fentanyl base, and bromazolam, cut with caffeine

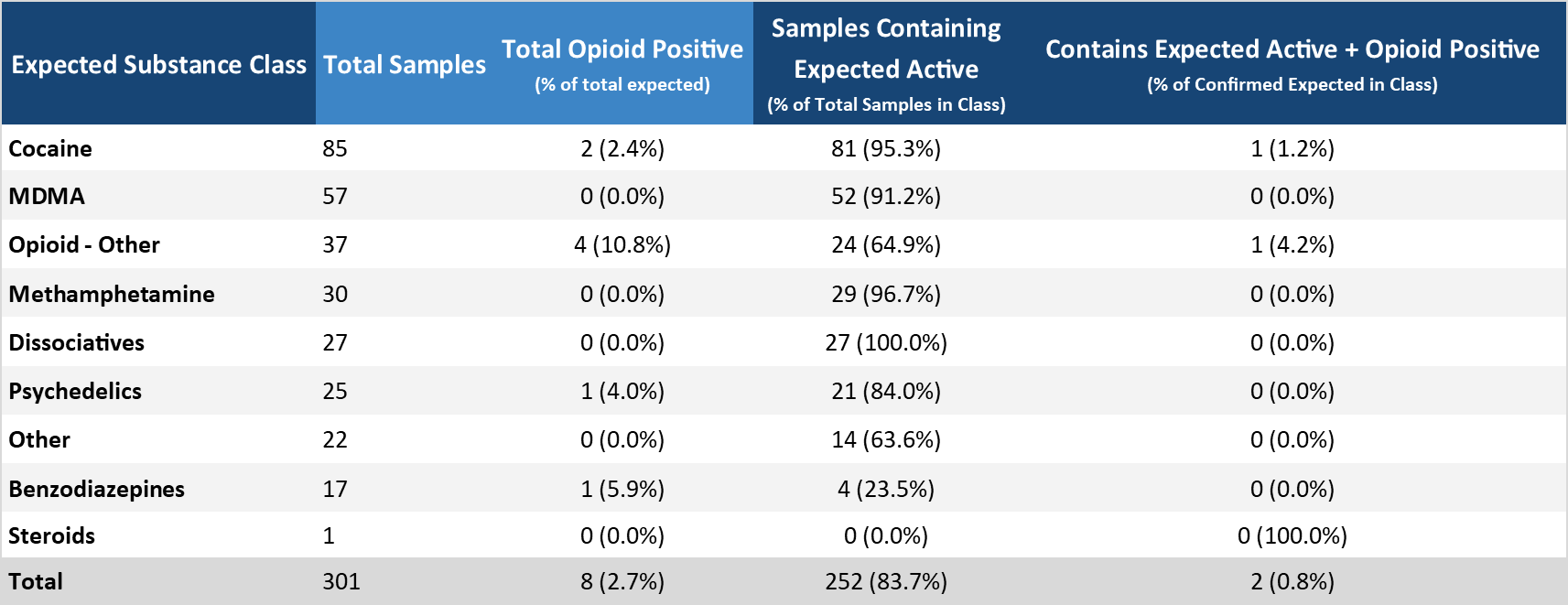

Opioid-positivity in non-opioid-down samples

In January, we checked 301 samples that were not expected to contain fentanyl or other “unexpected” opioids[1]. Since the opioid-down supply is no longer “just heroin” or “just fentanyl” and is instead a complex, potent, and ever-changing polysubstance market containing other synthetic opioids like fluorofentanyl or nitazenes, here we will examine the prevalence of any unexpected opioid, not just fentanyl, detected in non-opioid-down samples.

Specifically, we are excluding samples that were expected to be “opioid-down” or samples that had an “unknown/missing” expected composition. In the case of “opioid-other” samples, e.g. hydromorphone tablets and oxycodone pills, “unexpected opioids” are defined as any opioid that is not the expected opioid. ↩︎

Examining Table 3, we find that 9 samples tested positive for unexpected opioids in January, representing 3.0% of all non-opioid-down samples checked. These samples were as follows:

- 1 expected cocaine base sample tested positive for fentanyl or a fentanyl analogue via strip test only[1].

- 1 expected cocaine sample sample was consistent with a down sample and contained bromazolam, fentanyl, fluorofentanyl and xylazine instead of the expected cocaine base. Cocaine base samples are often most described as “white (or clear) crystals, this sample was described as “purple pebbles”.

- 1 expected Oxycodone sample contained fentanyl or a fentanyl analogue and oxycodone.

- 1 expected Percocet sample contained trace amounts of fentanyl cut with microcrystalline cellulose ( a common binding agent in pressed pills).

- 1 expected Hydromorphone sample contained N-desethyl isotonitazene instead

- 1 expected Hydromorphone sample contained an unknown fentanyl analogue instead

- 1 expected DMT sample contained fentanyl and bromazolam instead

- 1 expected unspecified benzodiazepine sample contained bromazolam, fentanyl base, and fluorofentanyl

In January, no unexpected opioids were detected in samples expected to be MDMA, methamphetamine, dissociatves, other, or steroids.

In people’s personal quests for bodily autonomy and informed consumption, there is often evaluation of risk and consequence, but when the consequences can be severe and the risks are unknown or are intentionally exaggerated, these become difficult, if not impossible, conversations to weigh. We believe that drug checking can help provide people with the information needed to evaluate the risks, and provides harm reduction advice to minimize undesired consequences of substance use. These data are not meant to downplay concerns or invalidate past experiences. We recognize the tragic consequences of when fentanyl is found in non-opioid samples and honour the heartbreak that such experiences produce. Instead, we present these data with the intent to combat misinformation and provide an evidence-based context for people to consider when making decisions about substance use. While these numbers reflect what we have seen over the course of the project, these (roughly) 1-in-100 events still occur, so we always encourage folks to get their stuff checked.

The presence of fentanyl in these samples is most likely due to cross-contamination with an opioid - down sample ↩︎

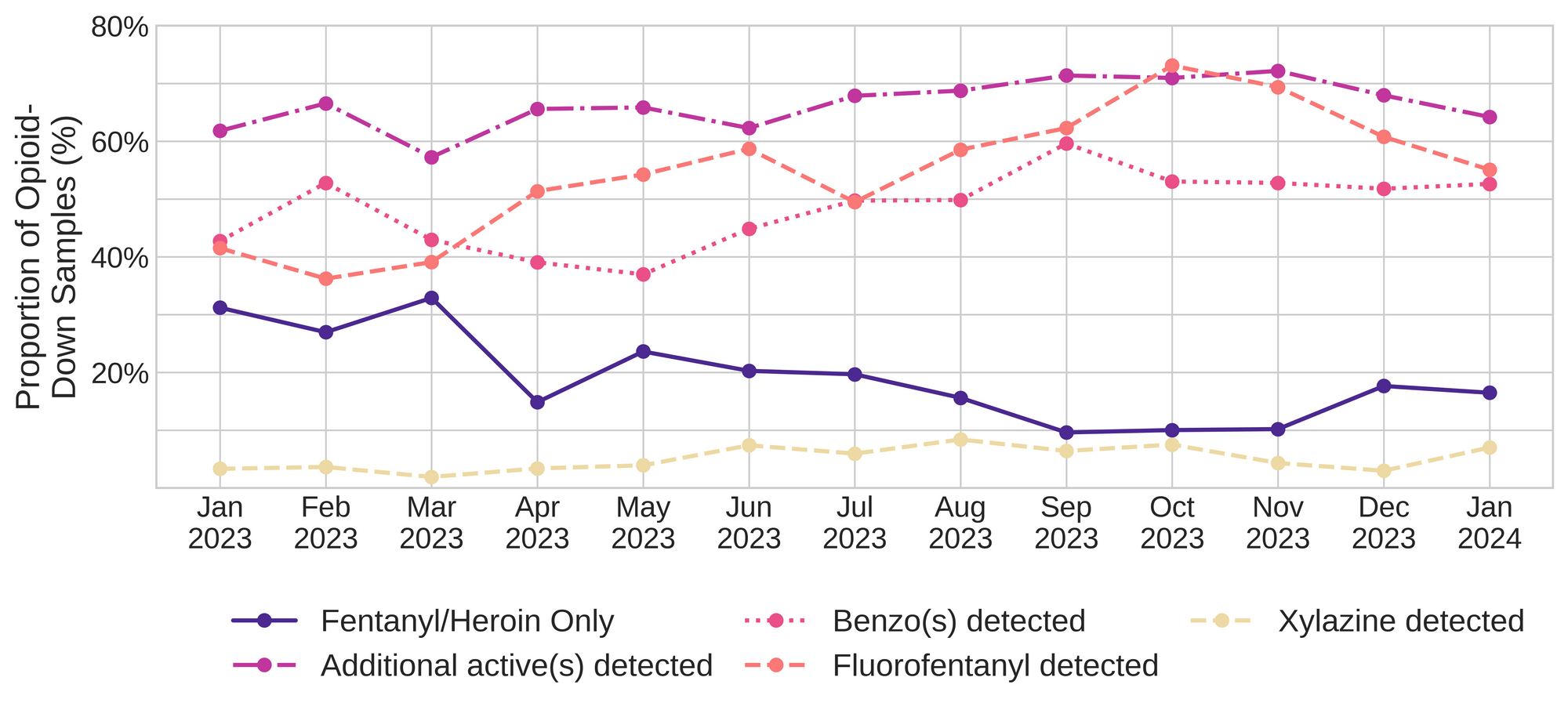

Opioid-Down (n=285)

In this section we present results specific to the opioid-down supply, therefore they may differ from the highlighted findings above that are inclusive of all expected drug categories.

85.6% of expected opioid-down samples contained fentanyl or fentanyl base (244/285)

57.2% of expected opioid-down sample contained fluorofentanyl or fluorofentanyl base (163/285)

21 samples contained heroin and/or related alkaloids to heroin such as acetylmorphine (MAM) or acetylcodeine (7.4% of expected opioid-down samples)

1 sample additionally contained morphine

17 samples included the one or more of the following additional actives: fentanyl, fentanyl base, fluorofentanyl, fluorofentanyl base, bromazolam, or etizolam

3 samples contained carfentanil

52.6% (150/285) of expected opioid-down samples contained a benzodiazepine

The most common benzodiazepine in opioid-down samples was bromazolam (110), followed by benzodiazepine (unknown type) (32), and flubromazepam (7).

Xylazine was detected in 7.0% (20/285) of opioid-down samples, most commonly being found in samples from Substance (8).

In January, 64.2% (183/285) of all opioid-down samples checked contained an additional active to the expected fentanyl/heroin. These data are shown in Fig. 3 highlighting the prevalence of benzos, fluorofentanyl, and xylazine in the down supply.

Fluorofentanyl was the most common additional active found within the opioid-down supply, with 55.1% (157/285) of opioid-down samples containing fluorofentanyl in addition to fentanyl. Additionally, fluorofentanyl was the only opioid detected in 12.0% (34/285) of opioid-down samples (i.e. no fentanyl or heroin was detected in these samples).

Benzo-related drugs contribute to a majority of the other additional actives found in expected opioid-down samples, with 52.6% (150/285) of expected opioid-down samples checked containing a benzo-related drug. Bromazolam continues to be the most common benzo seen in the down supply, with bromazolam being detected in 73.3% (110/150) of the benzo-positive opioid-down samples. Scattered detections of other drugs are still found and can be reviewed in the pdf report at the end of this blog.

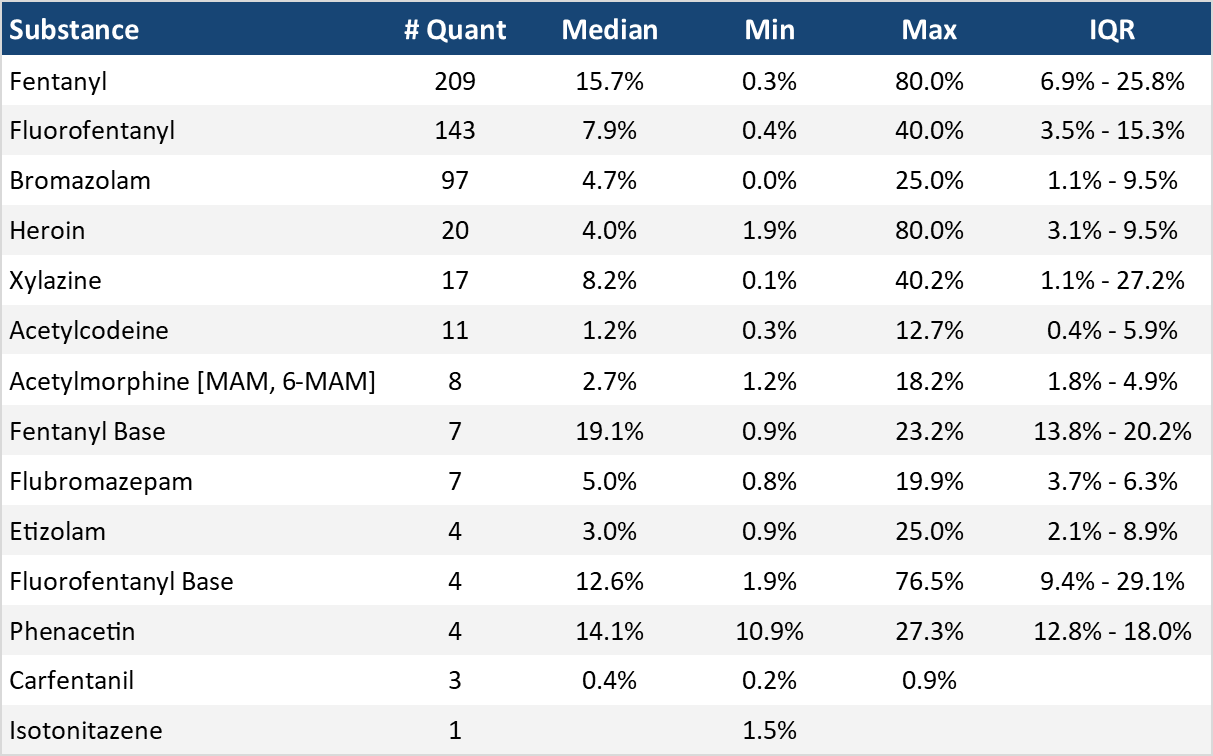

Quantification for Expected Opioid-Down[1]

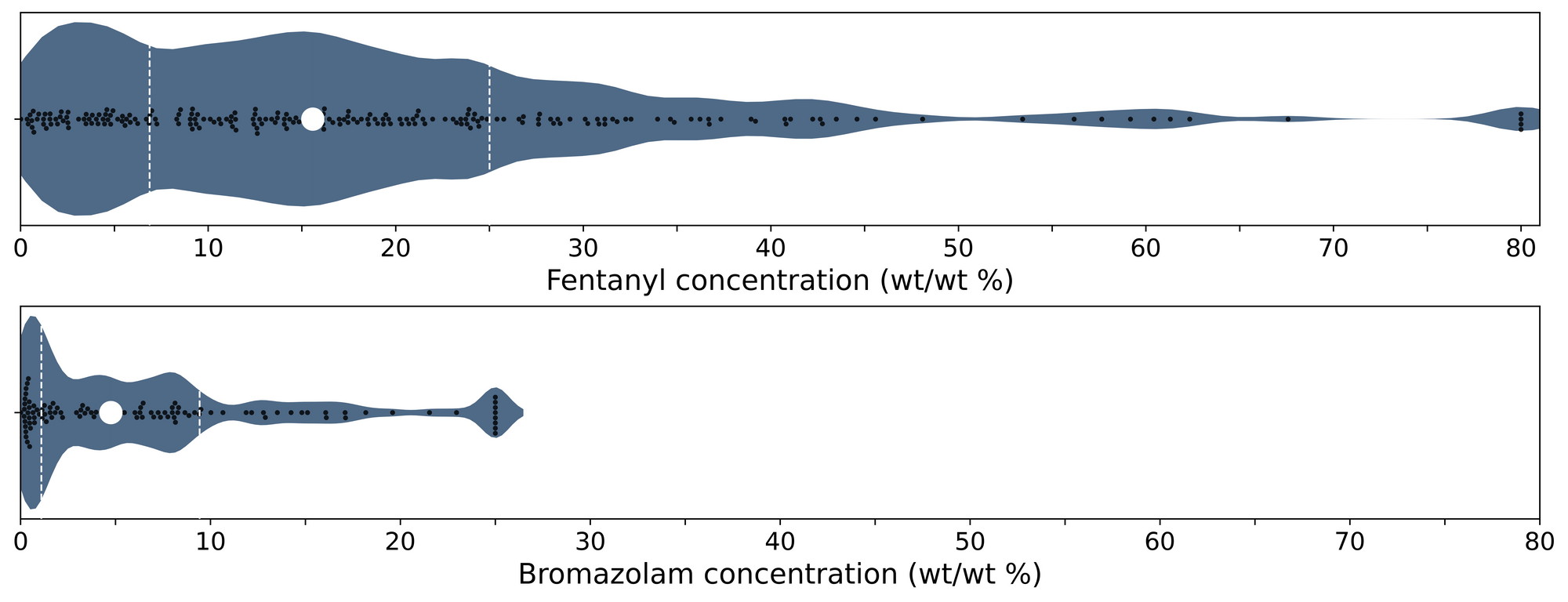

In January, we quantified fentanyl for 285 of the expected opioid-down samples containing fentanyl and found the median concentration to be 15.7%[2]. Though the median is a useful indicator, it doesn’t capture the volatility of fentanyl concentrations present in the opioid supply, as half of fentanyl-positive down samples contained between 6.9% and 25.8% fentanyl, and any one sample might be the lowest strength (0.3%) or the strongest (>80%[3]). Fluorofentanyl was seen at concentrations ranging from 0.4% to greater than 40%[3:1] as well, with a median concentration of 7.9%. Similarly, the concentration of bromazolam was across the board in expected opioid down samples, with samples ranging from less than 0.1% to greater than 25.0%[3:2] bromazolam, with a median of 4.7%. For context, a sample containing 4% bromazolam would be roughly equivalent to two full 2mg Xanax bars worth of benzo per point (100mg).

Not all opioid down samples brought to our service can be quantified. This is primarily due to too limited sample collected for our instruments to report a reliable mass percentage. Nevertheless, qualitative detection is still possible. ↩︎

This number is specific to fentanyl quantified in opioid-down samples. The median concentration listed in the Key Findings at the beginning of this blog (15.6%) is inclusive of all samples checked, across all drug classes and unknown samples, that contained fentanyl. ↩︎

For samples that contain greater than 80% fentanyl or heroin, greater than 40% fluorofentanyl, or greater than 25% bromazolam by weight, our mass spectrometer is presently unable to reproducibly assign a concentration due to the upper limits of the calibration methods currently adopted. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

The fentanyl and bromazolam concentrations that we quantified in January, across all expected drug categories and service models, are presented in Fig. 4. Small black dots are individual opioid-down samples, the large white dot shows the median concentration, dashed white lines bound half of the quantified samples, and the width of the shaded regions mirrors the number of samples at a given concentration.

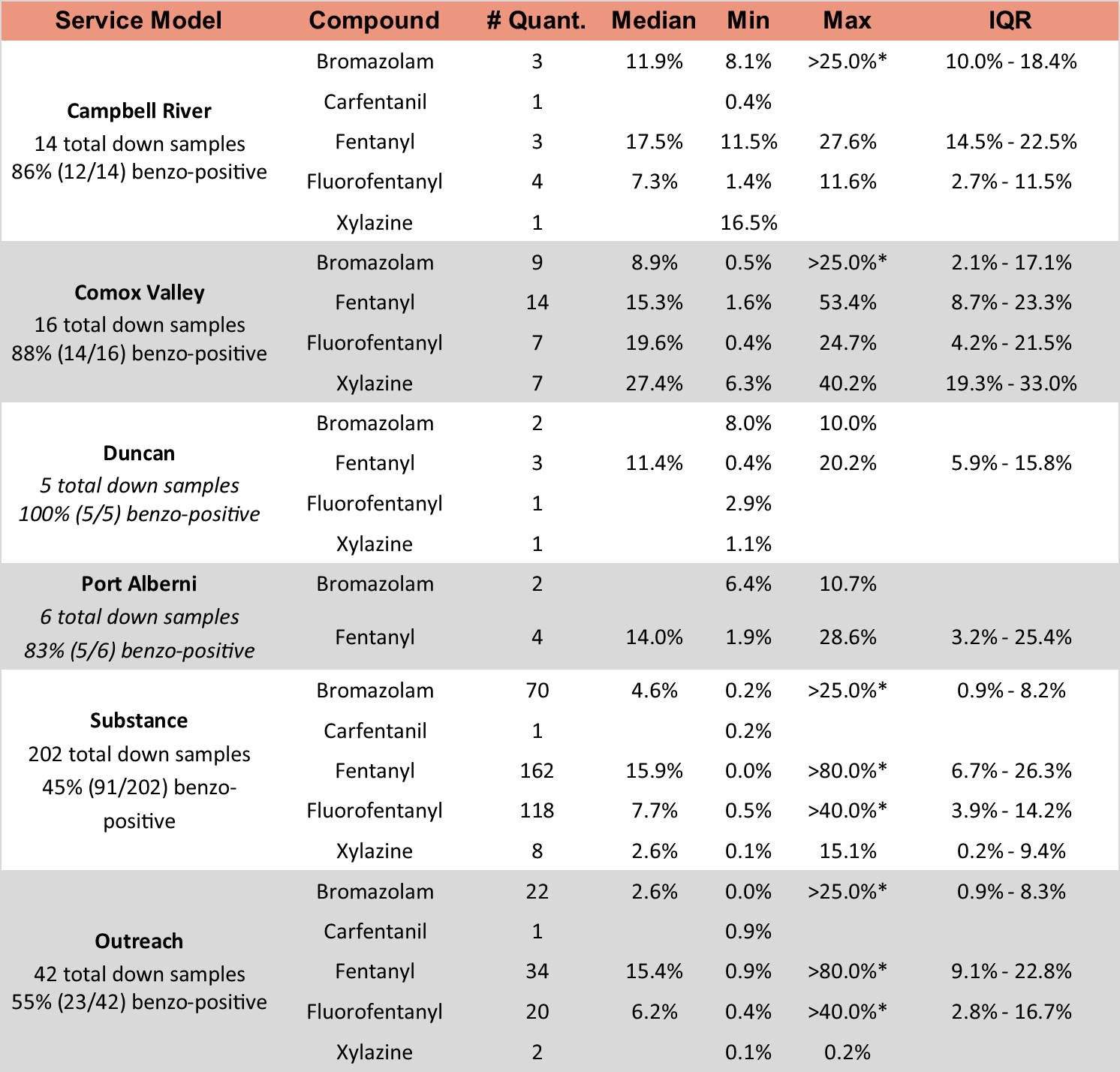

We can also examine the regional variability in the unregulated market. The table below expands on the quantitative data presented above. It focuses only on fentanyl, fluorofentanyl, carfentanil, bromazolam, and xylazine quantified within expected opioid-down samples, separated by collection location/model. Weight percentage is reported; “IQR” is the interquartile range: the range that contains half of the quantified samples.

Want to be notified when we release these reports? Join our mailing list to receive updates about when our reports are out. You can subscribe and unsubscribe yourself from this list at any time.

Check back next month for the February report!

As always, send us feedback at substance@uvic.ca on how we can continue to offer our drug checking results in a useful way.